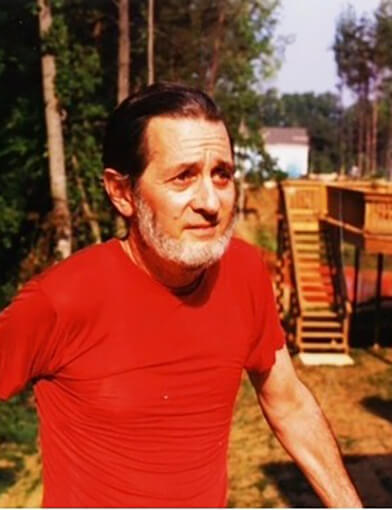

Friends of Stanley P. Bohrer, MD, MPH, described him as patient, thoughtful, generous, adventurous and content, a humble and quiet man who lived a meaningful life that he filled by traveling the world, collecting art and helping others through medicine.

“As I gained the wisdom of maturity, I realized that success is being content with life as it is,” he once said. He spent 17 years as a faculty member in radiology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine before retiring in 1998 as professor emeritus.

Bohrer died in 2022 at age 88 and left dual legacies that are consistent with how he approached life. Earlier this year, distributions from his estate endowed the Stanley P. Bohrer Distinguished Endowed MD Scholarship Fund. The scholarship will be awarded annually to Wake Forest medical students.

“Stan was an exceptional person in so many ways,” said C. Douglas Maynard, MD’59, former longtime chair of radiology at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine who helped recruit Bohrer to join the faculty.

An Unconventional Life

Bohrer led an unconventional life that took him around the world.

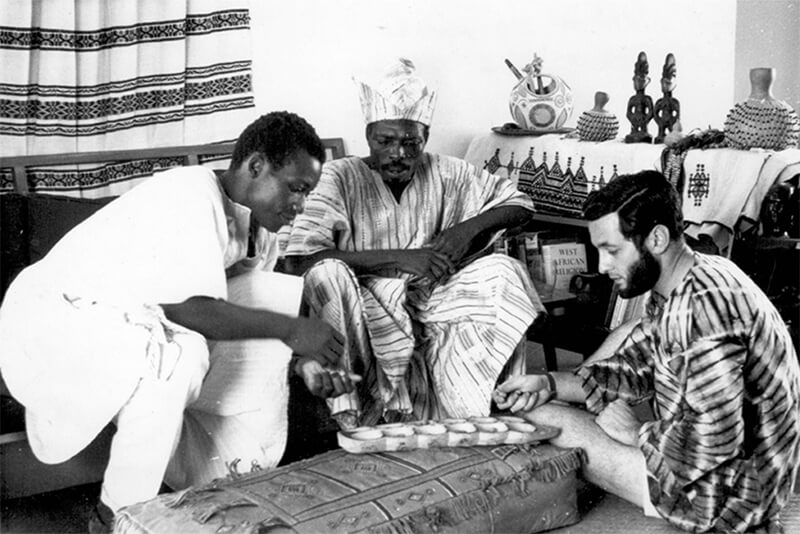

As a young man, he worked as a page at the U.S. Capitol, graduated magna cum laude from the University of Michigan and earned his MD at Harvard University as a cum laude graduate. After completing a radiology residency in Boston, Mass., and a year of postgraduate training in London, England, Bohrer spent 14 years as professor and head of radiology at University College Hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria. While there, he also served as a visiting professor in Ghana, Kenya and Tanzania.

He came back to America in 1975 to complete his master’s degree in public health, but he yearned for more travel. He worked with Project HOPE in Guatemala, Jamaica and Grenada, and when he came back to the U.S. in 1981, he joined Wake Forest University School of Medicine as a bone and trauma radiology specialist.

“When he joined our department, Stan added a completely new dimension,” Maynard said. Bohrer’s extensive international experience made him “an authority on radiology of tropical diseases, and it gave him a very different approach to our specialty,” Maynard said. “He often stated his expertise would be better called ‘poverty radiology.’”

Bohrer’s experience did not come without some danger. Maynard recalled that school faculty recruited Bohrer after his work in Guatemala ended abruptly. Bohrer had received a note from members of a guerilla military group in the region saying he was number one on their ‘hit’ list. “He left immediately, leaving most of his possessions behind,” Maynard said.

Bohrer remained an avid traveler, taking professional sabbaticals to teach at hospitals in Pakistan, India and Ecuador through the Radiological Society of North America. Professionally, he thrived, training medical students and future radiologists, becoming a fellow of the American College of Radiology and writing more than 100 scientific articles and the book, “Bone Ischaemia and Infarction in Sickle Cell Disease.” Maynard said that emergency medicine residents chose Bohrer as teacher of the year 4 times.

A Second Legacy

As he traveled the world, Bohrer made it a point to bring some of it back with him. His love of art, especially West African and Nigerian Yoruba art made by traditional artisans, led to an impressive collection.

He described his home as “literally filled with African sculptures and wood carvings,” including some made by his own hands. He was a lifelong sculptor who used hardwoods of Africa and Latin America as well as mahogany, teak and rosewood to carve bowls, plates, masks, busts, birds, abstract designs and more — even the mallets he used to do the carving.

The art he collected was generously donated to museums, including the Smithsonian Institution and Wake Forest University’s Lam Museum of Anthropology. Those works that inspired him will live as part of his legacy.

The rest of his legacy will resonate for generations. It will carry on through the lives of medical students whose careers his generosity will make possible and the lives that each of them will touch as physicians through the care and cures they bring to the world.

“Stan had a love for people that was readily apparent in his desire to make a difference in the lives of those less fortunate. He gave of his time, his resources and his knowledge eagerly and did not seek adulation, recognition or reward. He was a man at peace with himself. He was a superb member of our faculty for many years and made a difference in the lives of those around him.”

- C. Douglas Maynard, MD